Written by Jon M. DeVore and Carissa Siebeneck Anderson

Birch Horton Bittner and Cherot attorney Jon DeVore recently participated in a nationwide broadcast webinar on Winning in Relationships: Teaming; Mentor-Protege & Joint Ventures Webinar, hosted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Small Disadvantage Business Utilization (OSDBU), that targeted women owned Veteran Own Small Businesses (VOSB) and Service Disabled Veteran Owned Small Businesses (SDVOB). The webinar was chaired by the head of the VA OSDBU Women Owned Initiative and brought together Jon, another attorney and two owners of women owned businesses that were involved in construction and providing services to share their journeys and experiences with doing business in the Federal and commercial sector and providing legal advice to small and large business operating in this important sector of the economy. This OSDBU webinar is part of a series being conducted by the office to benefit small businesses.

The short article below was a portion of the presentations that were given during the webinar, but it was the real-life experiences of all of the participants that really gave life to the webinar. The article focuses on Teaming Agreements and Joint Ventures and Jon wanted to share this presentation hoping it would provide guidance and helpful suggestions for small businesses engage in teaming arrangements and doing business with the Federal government.

Non-Government Teaming Agreements

Teaming Agreements —

- The Teaming Agreement. A Teaming Agreement is a commonly used business development and marketing tool between a prime contractor and subcontractor who agree to combine resources to bid on a major government system procurement. Often, this agreement may include the actual bid of the subcontractor as an exhibit or describe the type of procurements to be pursued. Responsibilities and costs are often addressed.

- Enforceability varies State to State. In many states a teaming agreement is effectively an agreement to agree but not an enforceable agreement with consequences for breaching the agreement.

- For a contract to be enforceable, there must be (1) an agreement to all material terms, and (2) intention of the parties to be bound. Generally, a contract must be sufficiently definite as to its material terms such that the parties can be reasonably certain as to how they are to perform.

Agreement to All Material Terms

- In order for a teaming agreement to be more than an agreement to agree, DC law requires a definitive character of the obligation to perform. This is not necessarily a precise description of the ways in which the obligation will be performed.

- The difficulty is that the concept of definiteness cannot be reduced to a precise, universal measurement. The standard is necessarily flexible, varying for example with the subject of the agreement, its complexity, the purpose for which the contract was made, the circumstances under which it was made, and the relation of the parties.

- Generally, the terms that need to be defined are: (1) an explicit identification of the work to be performed, (2) the compensation to be paid for the work and the payment terms, (3) the quantity of goods or services to be provided, (4) the duration of performance, and (5) the delivery or performance dates. An agreement to simply continue negotiations in good faith does not satisfy this burden.

Intent of the Parties to be Bound

Under DC law for instance, parties are not bound by preliminary agreements, unless the evidence presented clearly indicates that they intended to be bound at that point. This usually means that the parties have taken some action in furtherance of the negotiations.

- For example, the court has found parties intended to be bound when they signed a letter of intent and provided that defendant agreed to negotiate exclusively to sell his business to plaintiff, in exchange for a non-refundable deposit. Courts have also found an enforceable contract establishing a binding commitment to negotiate in good faith when: 1) plaintiffs and the District of Columbia signed a letter of intent to immediately commence negotiations; 2) parties negotiated an Exclusive Rights Agreement, though it remained unsigned; 3) the Mayor had received authorization from the D.C. Council to convey the property to plaintiffs; and 4) plaintiffs expended money and effort in reliance on the agreement.

Suggestions and Pointers:

- Determine if the TA is intended to be general in nature or for a limited purpose of time.

- Consider if the TA is to be exclusive to the parties and prohibit the parties from “bolting” to another competitor.

- Damages are very difficult to prove if there is a breach and the TA is enforceable.

- Consider including a liquidated damages clause in the TA.

- Consider specifying a choice of law that might make the TA more enforceable.

- Making the TA governing law “flexible” depending on where the work is performed could be unpredictable as the impact of that choice, and/or could result in ambiguity as to which state applies if the work involves more than one state.

- In many states, if the pricing is not settled upon in some way (think a rate sheet or something similar), then the agreement is often deemed unenforceable as a mere “agreement to agree.” Other aspects are certainly more concrete (e.g., non- solicitation of employee provisions, IP, etc.). Often pricing is not agreed upon at this stage, but it should be a goal to get something included even if you negotiate it away later.

- Third party costs could be addressed in a TA. The third-party clause should, of course, be optional, but it can act as a decision-point as to whether you want to share third party costs with the teaming partner or bear your own costs. Sharing third-party costs is much more likely (and certainly appropriate) in a JV scenario, but much less common in the prime-sub scenario.

- A non-solicitation provision in the TA is good. You likely cannot limit the ability to hire employees from openly publicized postings, even if it is just for jobs related to the project, but it’s a deterrent even if not necessarily enforceable.

Types of Joint Ventures

- Traditional Small Businesses JV: A joint venture is when two or more small business concerns submit an offer as a small business for a federal procurement. The procurement may be bundled or non-bundled.

- Traditional 8(a) Procurement JV: An 8(a) concern partners with one or more other small business concerns as a joint venture on an 8(a) procurement. See 13 C.F.R. § 124.513(b).

- Mentor-Protégé JV: Two firms are in an SBA-approved Mentor-Protégé agreement. This can be under the All Small MPP. The JV’s eligibility for federal contracts will be based on the Protégé’s eligibility (e.g. 8(a), small business, WOSB, etc.).

Joint Ventures: An Overview

- Joint Venture = limited-purposed business ventures for joint profit where an association of individuals and/or concerns with interests in any degree or proportion consort to engage in and carry out contracts.

- JVs are temporary. For this purpose, joint venture participants combine their efforts, property, money, skill, or knowledge, but not on a continuing or permanent basis for conducting business generally.

- SBA New Limit on JVs is unlimited contracts in 2 years. Under new SBA regulations, JVs are no longer limited to no more than three specific contracts over a two-year period.

- Managing Venturer (MV) must be the Small Business/8(a).

- Small Business/8(a) must own at least 51% of the JV.

- Each JV partner must receive profits commensurate with the work it performed.

- Small Business/8(a) must perform at least 40% of the work performed by the JV.

SBA Approval – 8(a) v. All Small:

- 8(a) MP JV and All Small MP JV: As with all 8(a) JVAs, the JVA must be in place before the award can be accepted by the JV, but for ONLY 8(a) Sole Source Awards must the SBA approve in advance. This changed with the proposed SBA Regulations changes.

- All Small MP JV: SBA approval of the JVA is not required. However, the JV partners will likely be required to submit certifications of compliance to the procuring agency e prior to performance of a JV All HUBZone, SDVOB, and WOSB: All participants can benefit by teaming and Joint Ventures.

MP Agreements

A joint venture of at least one SBA participant and one or more other business concerns may submit an offer for a competitive procurement without regard to affiliation, if it meets the following requirements:

- Small: each concern is small under the size standard corresponding to the NAICS code assigned to the contract. 13 CFR 121.103(h)(1)(i).

- Size Mentor-Protégé JVs: Two firms approved by SBA to be a mentor and protégé under 13 CFR 125.9 (All Small MPP) of this chapter may joint venture as a small business for any Federal government prime contract or subcontract, provided the protégé qualifies as small for the size standard corresponding to the NAICS code assigned to the procurement,and the joint venture meets the requirements of § 124.513 (c) and (d) (8(a) protégé), § 125.8(b) and (c) (Small Business protégé), § 125.18(b)(2) and (3) (SDVO SBC protégé), § 126.616(c) and (d) (HUBZone protégé), or § 127.506(c) and (d) (WOSB/EDWOSB protégé), as appropriate.

BENEFIT:

Agencies get teams of small businesses with complementary capabilities instead of one small business. This allows agencies to push more work with greater value and greater demands to small businesses, which in turn makes it easier for agencies to achieve its general and specific small business contracting goals for each year. In addition, agencies benefit specifically on that contract from getting the increased stability, greater expertise, more extensive past performance, and greater capacity of having two or more small businesses working as a team to meet the government’s contract requirements.

Performance of Work Requirements for JVs

Two levels of performance of work requirements:

Performance of Work: The Managing Venturer (senior JV partner) must perform certain percentage of total work performed by the JV partners (i.e. of the JV’s work). Limitations on Subcontracting: Minimum amount of work that the JV (serving as the “Prime”) must perform of the total contract’s work (generally applicable).

JV Protégé Performance of Work Requirements & Subcontracting Limitations for JVs

Protégé’s Performance of Work – Current Performance of Work Requirements for 8(a) Mentor-Protégé Joint Ventures

- For any 8(a) contract, the JV must perform the applicable percentage of work required by 13 CFR § 124.510, which references 13 CFR 125.6, with percentages applicable to any small business contract.

- In an unpopulated joint venture both the 8(a) and non-8(a) partners are technically subcontractors.

8(a) JV partner(s) must perform at least 40% of the work performed by the joint venture.

- Work performed by 8(a) JV partners must be more than administrative or ministerial functions so that they gain substantive experience.

- Work done by the partners will be aggregated and the work done by the 8(a) partner(s) must be at least 40% of the total done by all partners.

- In determining the amount of work done by a non-8(a) partner, all work done by the non-8(a) partner and any of its affiliates at any subcontracting tier will be counted.

Subcontracting Limitations:

JV = Prime Contractor. For purposes of compliance with subcontracting limitations, the JV is considered the Prime, so the work done by both/all JV partners will determine how much work is performed by the “prime” compared to subcontractors.

Example: On a Services contract, the JV must perform at least 50% of the contract’s award amount received by the JV contractor, and the protégé must perform at least 40% of the work done by the JV (thus protégé performs at least 20% of the services portion of the contract value).

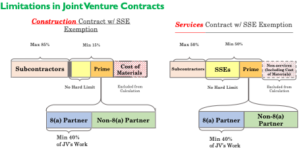

The chart below is a good illustration of how the various forms of joint ventures and mentor protégé joint ventures can and must allocate the work between the J/V partners and other third parties.